From Lab Technique to Orbital Staple

Freeze-drying (lyophilization) preserves food by removing moisture while it remains frozen, preventing cell collapse and helping retain color, shape, and nutrients. The method migrated from pharmaceutical use into foods and then into human spaceflight as a practical answer to mass, volume, and safety constraints.

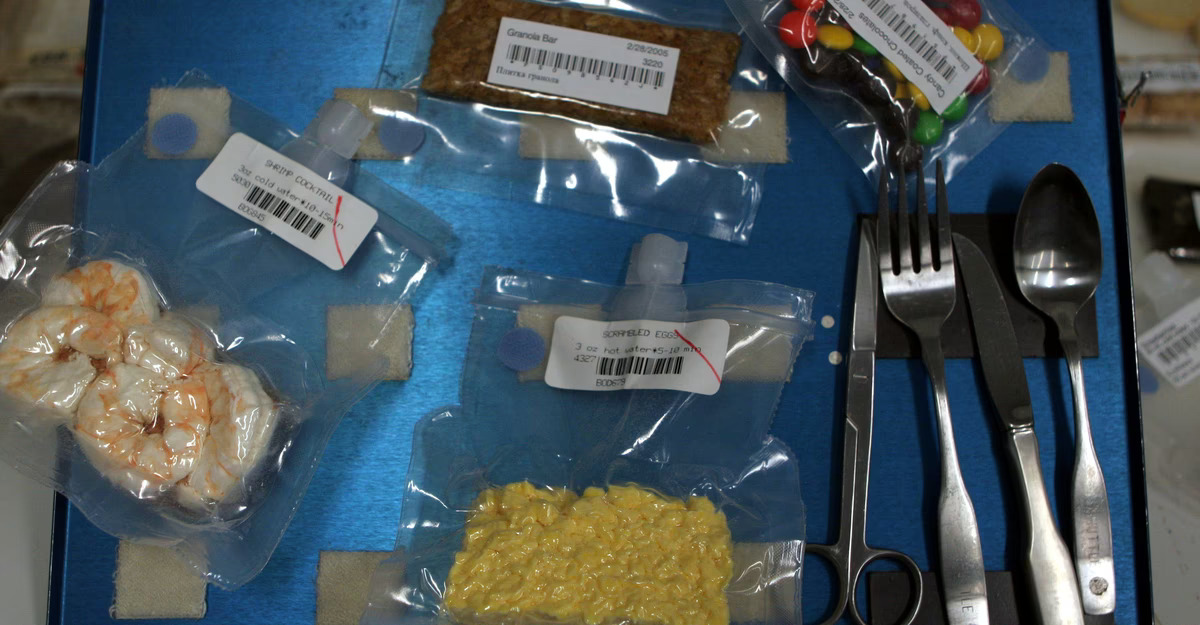

Early programs set strict criteria—room-temperature shelf life, compact form, low mass, and quick, low-effort prep. Preservation approaches NASA examined included dehydration, freeze-drying, intermediate moisture, irradiation pasteurization, and nitrogen packing. Mercury-era crews tried bite-sized cubes, freeze-dried powders, and semi-liquids, which were hard to rehydrate and created floating crumbs in microgravity.[1]

Why Astronauts Still Use It

By removing nearly all water, freeze-dried meals cut launch mass, extend shelf life without refrigeration, and rehydrate with minimal equipment—advantages that remain relevant even as modern spacecraft galleys improve. On the International Space Station, for example, crews may have fridges and ovens, yet freeze-dried entrées and sides are still part of the menu mix because of their reliability and efficiency.[1]

Cold-water readiness: NASA set a goal for foods to reconstitute in roughly 80°F (27°C) water within 10 minutes; specially developed gravies reached full rehydration in about 5 minutes.[1]

How Freeze-Drying Works

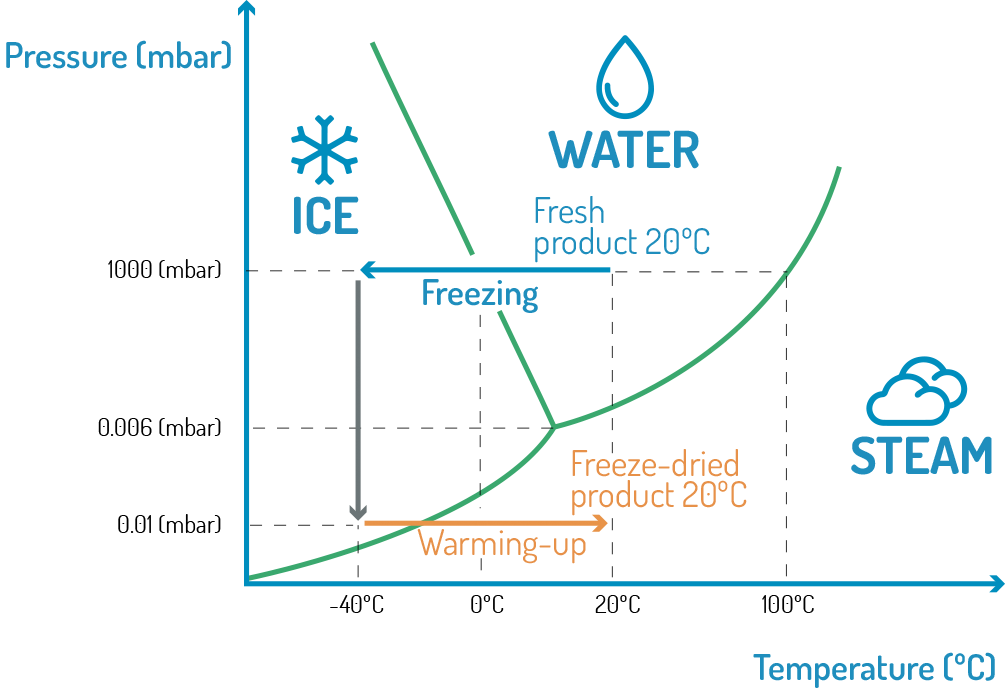

Food is frozen (about −40°F), placed in a vacuum chamber, and gently warmed so ice skips the liquid phase and turns directly into vapor (sublimation). Water vapor is removed and the cycle repeats many times until the product is essentially dry. Typical cycles span roughly 8–24 hours and can remove more than 99% of the original water.[1]

Nutrition, Texture, and Taste

Because freezing supports the food’s structure during drying, rehydrated items can maintain appealing texture and flavor. Compared with conventional dehydration, which usually removes ~92–96% of moisture, freeze-drying’s >99% removal yields lighter packs, faster rehydration, and better retention of minerals and other nutrients.[1]

Culture Note: The Truth About “Astronaut Ice Cream”

The famous freeze-dried ice cream began as a public-facing novelty in 1973 tied to the Ames Visitor Center. It leveraged space-driven process advances but wasn’t standard astronaut fare. The story nonetheless helped popularize freeze-dried treats with museum-goers and outdoor enthusiasts.[1]

What’s Next

Looking ahead, research focuses on smarter drying profiles for faster, more even rehydration, targeted micronutrient stability, and mission-specific menus. The goal is familiar: maximum nutrition and morale, minimum mass and waste.

FAQ

What made freeze-dried foods attractive for early spaceflight?

They fit the brief: shelf-stable at room temperature, compact, lightweight, and easy to prepare with little water or equipment—ideal for microgravity operations.

How is freeze-drying different from conventional dehydration?

Dehydration removes ~92–96% of water; freeze-drying removes >99%. The result is lighter payloads, quicker rehydration, and generally better nutrient retention.

Do astronauts really eat freeze-dried ice cream?

No—it originated in 1973 as a museum novelty connected to NASA’s Ames Visitor Center rather than as standard space food.

What does the process involve?

Freeze to around −40°F, apply vacuum, add gentle heat so ice sublimates to vapor, repeat cycles until water is essentially gone (typically over 8–24 hours).

Can crews rehydrate meals with cold water?

Yes. NASA targeted ~80°F (27°C) water with a 10-minute window; specific formulations like gravies hit ~5 minutes.

References

- NASA Spinoff (2020). Freeze-Dried Foods Nourish Adventurers and the Imagination. https://spinoff.nasa.gov/Spinoff2020/cg_2.html

Post time: Nov-12-2025